For an unknown number of people, their heart disease is caused by a condition called “ATTR amyloidosis.” For this widely under-diagnosed, progressive and often fatal disease, there are few options for treatment.

When the protein transthyretin (TTR) falls apart, it can clump together and morph into amyloids – a cluster of misfolded proteins that stick together. These are acutely dangerous when deposits form in the heart, as they can result in amyloid-TTR amyloidosis (ATTR amyloidosis): a type of heart failure long hidden in the shadows, poorly studied.

Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Senior Scientist Avi Chakrabartty says the problem of ATTR amyloidosis being under-recognized is compounded by the fact that standard heart medications – including blood thinners, statins and digoxin – may not work, and may in fact be harmful.

“There seems to be an unmet need for diagnosis and treatment,” Chakrabartty says. “That was the impetus for starting the research.”

His lab discovered an antibody target that is hidden when a protein acts normally, but exposed when it falls apart. Less than a decade later, this set the stage for a novel clinical trial that began late last month.

Research at Lightening Speed

The idea was whether the antibodies they found, quickly validated, could help to diagnose ATTR amyloidosis – and even treat it. What sets this work apart is that these antibodies can attach to amyloid plaque, prevent growth, and induce the body’s immune system to wipe them out.

“While some drugs suppress the production of amyloid, the antibodies we found actually clear the misfolded proteins and tag the deposits for immune destruction,” says Chakrabartty.

This quickly caught the eye of Prothena, a global biotechnology company, which funded the work at the ground level. Prothena brought to the table an ability to turn polyclonal antibodies into monoclonal antibodies – the type that can be turned into new medications.

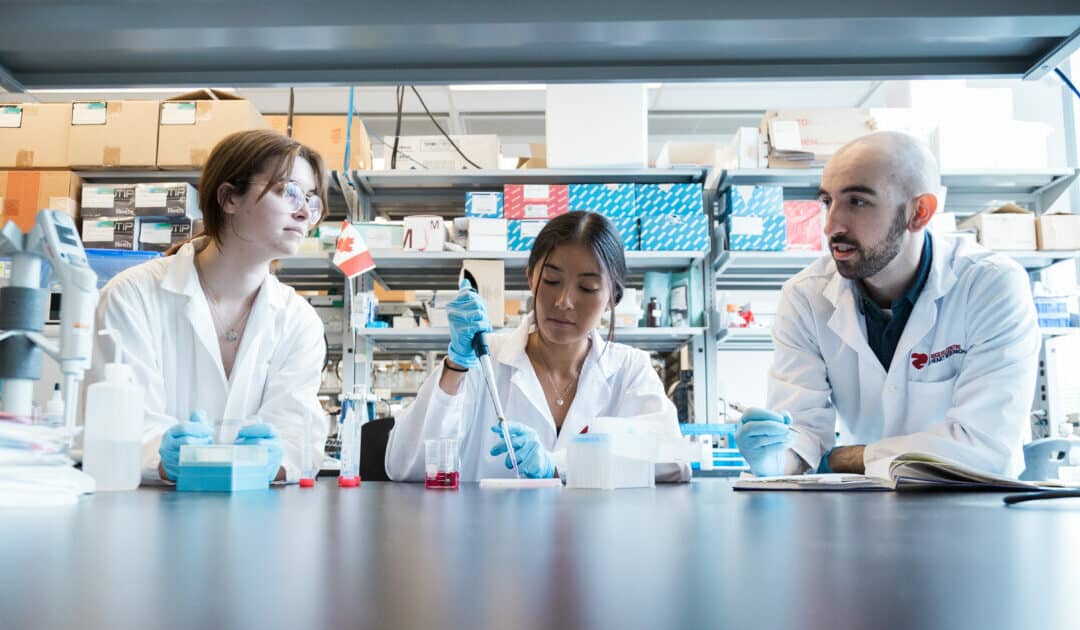

The Ted Rogers Centre entered this picture by providing an Education Fund award to Chakrabartty’s trainee Natalie Galant, adding further momentum to this work. The Centre’s widespread community, as well as our annual conference, opened new clinical contacts to them, propelling the research forward.

“Without the Ted Rogers Centre, we would not have created the collaborations we did here at University Health Network,” Galant says.

‘We are going to go all the way’

With Prothena’s involvement, they ensured the monoclonal therapy was safe and non-toxic for people, and secured FDA approval to begin recruiting for a clinical trial.

In Phase 1, underway now, ATTR amyloidosis patients will receive a low dose to see how it is tolerated. After its safety is established, they will gradually increase the dose, and start to measure its effectiveness. Phase 1 is slated to finish by the end of 2019.

The next phases could involve UHN, a partner of the Ted Rogers Centre. Chakrabartty is confident they are onto something big here.

“We are going to go all the way,” he says. “If everything keeps going at this pace, we hope it will be only five to six years until FDA approval.”

A genetic link

One fascinating possibility is tied to the genetic origins of ATTR amyloidosis. The disease’s genetic mutations – for which we know African-Americans seem to have a much higher rate – can cause the misfolded proteins, but the age of onset varies.

If someone has a family history of this disease, and genetic tests uncover this mutation, it could lead to the possibility of genotyping patients. The antibodies uncovered in the Chakrabartty lab could one day provide a preventative therapy for these individuals – long before symptoms develop.

*******

At top: Natalie Galant and Avi Chakrabartty