Maria Flores knew she had a congenital heart problem, but it wasn’t until age 17 when, after some tests, a cardiologist put a name to it: fibromuscular subaortic stenosis – a growth constricting the region just below her aortic valve. It was, though, something Maria thought she could likely live with without complications – and indeed, she’s never had any.

In her 30s, Maria wanted to start a family. Now a patient of Dr. Rachel Wald, a cardiologist at Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, Maria was sent to the Special Pregnancy Program at Mt Sinai Hospital because of her heart defect – as heart disease in pregnancy can put both mother and fetus at higher risk of adverse events.

“Dr. Wald and the team at Mt Sinai saw me through each pregnancy, and kept me well informed of everything that was happening,” Maria says. “I am blessed to have such good care.”

For Maria’s first pregnancy, everything went according to plan. For her second pregnancy, however, measurements showed worsening of her subaortic stenosis. Dr. Wald invited Maria to join a new study that sought answers to questions about the link between cardiovascular health of expecting mothers and their unborn babies.

The Challenge

Today, more and more women with heart disease are having children, meaning we must learn more about the link between pregnancy and the risk for adverse events to provide optimal care to this expanding population.

Dr. Wald says that insufficient cardiac output (blood flow from the mother) can result in clinical compromise in some pregnancies. The problem is that we don’t know how to assess adequacy of cardiac output nor do we understand what is sufficient flow for the fetus.

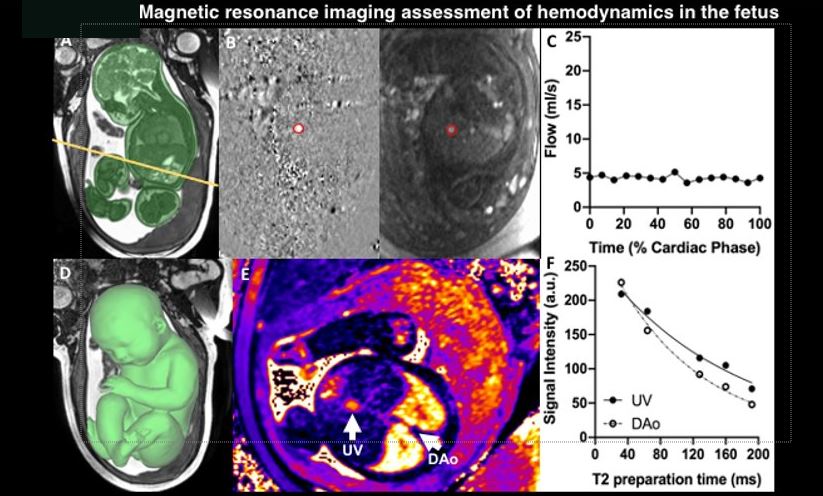

While some early studies used echocardiography to measure cardiac output, the gold standard for measurement of flows remains cardiac MRI. Recent advances in this technology means we can dig deeper than ever before, at a far more granular level.

But cardiac MRIs are seldom used to assess cardiac output in pregnancy, because doctors don’t know when to order studies or how to interpret the information.

The Findings

In this collaborative study that includes members of the Ted Rogers Centre, researchers used state-of-the-art MRI in mothers with moderate to severe heart disease to assess blood flow inside both mother and fetus – and any connection to adverse heart problems.

In 22 women, including Maria, the team was able to measure cardiac output at different points during and after the pregnancy. For the fetuses, they also measured basic cardiac output as well as their oxygen levels.

“We were surprised to learn that most moms with heart disease augmented their cardiac output compared to healthy controls,” says Dr. Wald. “We did note that those moms who went on to have adverse cardiovascular events in pregnancy were those who couldn’t adapt to pregnancy with the anticipated increase in blood flow.”

A reassuring finding was that all babies had favourable outcomes regardless of the severity of their mother’s heart disease or any related cardiovascular events.

What it Means

This study demonstrates that cardiac MRI can in fact be used to determine vascular flows in mother and fetus.

Dr. Wald says one of the main takeaway messages from this pilot study is that there is no cause for concern for the fetus. “They have the same oxygen and flow delivery, and are generally not born earlier or smaller despite their mom having cardiovascular disease,” she says.

What’s next: understanding in a broader population whether we can use MRI as a tool to help predict if a pregnant woman with heart disease will not be able to augment her cardiac output and thus is at greater risk for adverse cardiovascular events.

The study also showed that uniting diverse specialists – cardiologists, obstetricians, imaging experts, and others – in unique collaborations can truly move the needle in research.

Maria is now a 38-year-old mother of three young children. Her aortic valve did tighten again in the third pregnancy, but she and the baby had no negative effects. She says she is proud to be part of Dr. Wald’s study.

“I know how important research is to make discoveries that help people in the future,” Maria says. “In this case, helping benefit moms with various heart conditions before, during, and after pregnancy.”