In the September 2021 issue of European Heart Journal members of our team published an important study on the value of a medical procedure in heart failure. This story is informed by first author Dr. Leah Kosyakovsky and lead author Dr. Douglas Lee.

The Challenge

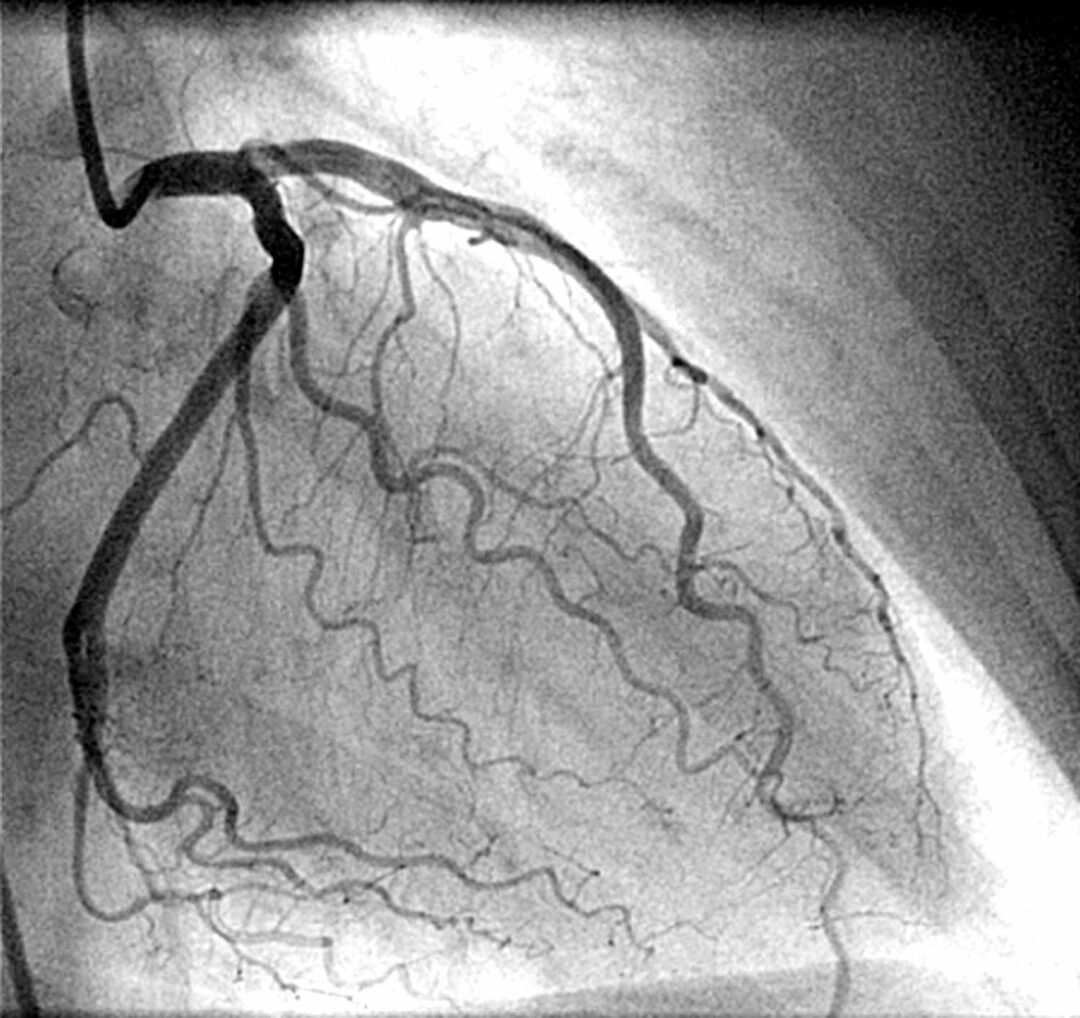

Coronary angiography is a technique used to study the main arteries supplying blood to our heart – and in particular, to diagnose the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD). The goal is to identify arterial blockages that would make patients prone to heart attacks, and certain procedures may then be performed to reduce these risks.

Yet angiography is potentially underutilized in identifying CAD linked to heart failure – despite CAD being implicated in two of every three cases. At the moment, there is limited evidence guiding whether physicians should perform an angiogram for patients who arrive with acute heart failure flare-ups. Given that symptoms of acute heart failure overlap with symptoms of CAD, understanding what is behind a patient’s presentation is critical.

Today, only one in 10 patients admitted for acute heart failure in Ontario undergo short-term angiography. Should it be more?

The Study

Ted Rogers Centre investigators studied 3,000 patients with acute heart failure, half of whom had an angiography within two weeks at the hospital. To identify those who are higher risk for underlying CAD, they included patients with at least one of three key factors: prior heart attack, current chest pain, or high levels of troponin (a protein where high amounts suggests heart damage from CAD or heart failure).

The team found that those who had angiography within the two weeks had, two years later, significantly reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and hospitalizations for heart failure. This was the case for both new heart failure cases and those who were having flareups of existing heart failure.

What it Means

This observational study demonstrates that the early use of angiography was associated with improved long-term outcomes of heart failure patients suspected of having underlying CAD. This could be due to increased revascularization of identified CAD or potentially through changes in the prescription of medications used for CAD.

This study suggests that angiography is a valuable and potentially underutilized tool in diagnosing and managing CAD in acute heart failure, where scant evidence exists to support clinical guidelines. Specifically, in the right clinical context, angiography should be considered as an ongoing way to evaluate whether CAD could be contributing to heart failure exacerbations, rather than a one-off test only used at the first diagnosis of heart failure.